|

|

|

|

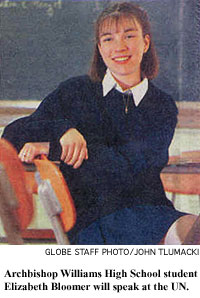

By Sandy Coleman Elizabeth Bloomer is a typical teenager, putting her jeans on one leg at a time. But she checks the label first to make sure her clothes are not from a country or company suspected of using child labor. The 15-year old has so passionately pursued the fight to end child labor abuses worldwide and has become such a well-spoken advocate that today she will address the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, sharing the day with more famous speakers. While school projects come and go, young attention spans wane, and trends change quicker than you can say "New Kids on the Block," Bloomer has held on tightly to the cause she and her classmates took on four years ago as students at the Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy. It began with a story about a little Pakistani boy. Twelve-year-old Iqbal Masih freed himself from slavery in a carpet factory, fought to get more than 3,000 other children to do the same, came to the United States to accept an award, and became a symbol of the fight against child labor, only to be murdered while riding his bike outside his grandmother's house in Pakistan on Easter Sunday 1995. When Bloomer first heard Masih's story, she was moved to stamp out child labor. She hasn't stopped moving since. "I know it's real, and it's not just something that happens in another country where I can't do something about it," insists Bloomer, now a student at Archbishop Williams High School in Braintree. "I've also realized the power kids have to make a difference, so that encourages me." At her new school, the honors student began a chapter of a national organization, Operation Day's Work, that has raised thousands of dollars to support children in developing countries. Bloomer's speech to the United Nations today is the latest in a public-speaking career that began when she was 12. She has spoken to a congressional roundtable in Washington, D.C., and at Harvard University and other colleges. |

With her middle school classmates, Bloomer has also lobbied senators to ratify a new international treaty to discourage child labor, which affects about 250 million children ages 5 to 14. "She's been a relentless voice," said Ron Adams, the seventh-grade language arts teacher whose class Misah visited when he came to the United States. "Elizabeth was a big part of getting kids to be aware of this global treaty." President Clinton signed the treaty in 1999, and it took effect two months ago. Bloomer boldly speaks out on behalf of other children, but she is quieter when it comes to blowing her own horn. She continually shifts the focus to her classmates and Adams when asked about the attention her advocacy is drawing. The students still meet on weekends to work on child labor issues, she said. "I never intended to be a spokesperson," she says. "There are lot of kids who are spokespersons, too." Bloomer's passion is driven by a family rule: "Once they are involved in something, we don't let them quit," said her mother, Roberta Bloomer, who has six other children, ages 14, 12, 10, 8, 5, and 13 months. At the UN, Bloomer will speak before 900 high school delegates from around the world. Her 25-minute speech will be broadcast on the World Wide Web, and her words translated into six languages. She will plead that more be done to help children. And, she will tell the story of Iqbal Masih and how his life and death spurred her middle-school classmates to raise more than $100,000 to build a school in Pakistan to honor him. "One of our mottos is: A bullet can't kill a dream," she said. "I thought that was horrible that someone would shoot a little boy, probably for standing up for what's right...We're his voice." |