|

"A School for Iqbal"

Back when life was supposed to be less complicated, one thing really was simpler. The accepted method for teaching American kids about the economy of a foreign country was fairly straight-forward. Each student wrote a one-page report, drew a "product map," and maybe brought in a "typical" food from an assigned country. Kids who reported on Holland or Switzerland always had an advantage because they could win the class over with Dutch or Swiss chocolate. |

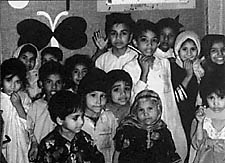

Pakistani working children attending Iqbal's school in Kasur, Pakistan. |

|

It's not that simple anymore. The world's economies are much more complex, and individual nations are more interdependent than ever. "Competing in the global marketplace" is the credo of American business. But in the global marketplace economic, political, and cultural concerns are often intertwined. A product map showing that Norway exports herring and Sweden manufactures high quality steel offers little guidance when the issue in question is whether or not human rights concerns should affect trade relations between two countries. Take the ongoing ambiguity over what constitutes fair treatment of workers. Labor practices considered acceptable in one country might be condemned as abusive in another. For example, Americans would be outraged if a nightly newscast were to report that ten-year-old American children were being chained to factory equipment and forced to work 70 hours a week. But what if the report concerned Pakistani children in a Pakistani factory? How, then, would we respond? When an American consumer thinks about buying an imported product, should human rights issues or working conditions in the country of origin make a difference? Or should price and quality be the only things that matter? And in teaching international economics to American students in grades K-12, is it legitimate, or perhaps even necessary, to go beyond the study of such basic economic concepts as "comparative advantage" and examine these topics in the context of more complex issues, such as human rights? Students and teachers at Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy, Massachusetts, grappled with those questions, and their search for answers turned into a multi-year lesson in international economics. It all started when Ron Adams, a longtime language arts teacher with a deep interest in human rights issues, invited Iqbal Masih to visit Broad Meadows on December 2, 1994. The 12-year-old Pakistani was in the United States to accept the Reebok Human Rights Award for his efforts to focus international attention on child labor abuses. Iqbal's activism sprang from his own experience in a Pakistani carpet factory. At age four, his family sold him into bondage for $12 - a practice not uncommon n Pakistan, where en estimated 7.5 million children toil as bonded laborers. He was forced to work form 4 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week. Sometimes he was chained to his carpet loom; all too often he was beaten. Confinement and malnutrition had so stunted his growth that he was half the size of an American 12-year-old. When he was ten, Iqbal slipped away form the carpet factory to attend a rally where he spoke publicly of his six years as a bonded laborer. He then refused to return to his owner and began organizing a campaign against child labor. Both his refusal to return to work and his organizing efforts exposed Iqbal and his family to the possibility of retaliation form those who benefited form using bonded labor. Although his experiences were far removed from those of an American 12-year-old, Iqbal's story had an immediate and dramatic impact on the students at Broad Meadows Middle School. Shortly after his visit, they sent 400 letters to the prime minister of Pakistan and another 150 letters to Massachusetts' two senators. They also contracted 60 local carpet merchants to ask about their policies on selling rugs make by children. Compelling as they were, the words of a 12-year-old Pakistani boy might not have had the same effect on another group of American kids. But the Broad Meadows students weren't just any group of kids. They had the advantage of working with an extraordinary group of teachers and supportive school principal. Even excellent teachers and an enlightened curriculum, however, were not enough to prepare Broad Meadows students for the shock they received upon hearing the news that Iqbal Masih had been shot to death near his village in Pakistan on April 16, 1995 - less than six months after visiting Broad Meadows. An investigation by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan concluded that his death was not related to his efforts to end child labor, but their ruling left many unconvinced. Regardless of why or how Iqbal had died, the students at Broad Meadows resolved to continue the work begun by the diminutive Pakistani boy who had visited their school and touched their lives. They decided that their memorial would be "A School for Iqbal." Their original goal was to raise $5,000 to build a one-room school where bonded child laborers in Iqbal's home village might acquire the knowledge that could ultimately help them improve their lives. Not only did the Broad Meadows students reach their goal, they went far beyond their original expectations and learned quite a bit in the process. They contacted schools via an educational computer link and asked for $12 donations (an amount symbolic of the fact that Iqbal was sold into bondage for $12 and slain at age 12). Contributions came from all 50 states and two dozen foreign countries. Students also enlisted the support of the rock group REM, which contributed $1,000 and invited the students to raise funds at three of the band's Massachusetts concert appearances. Two years after they began, the Broad Meadows students closed out their fundraising campaign with more than $147,000. In May 1997, the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan visited Broad Meadows Middle School to congratulate the students and help them celebrate the conclusion of their highly successful campaign. Because of their dedication and persistence, a four-classroom school today offers a measure of hope to more than 200 children in Pakistan's Punjab region. |

|

Iqbal's visit to Broad Meadows, December 1994. Left to right, back row: Stephan Allsop, Amanda Loos, Mr. Ron Adams, Mrs. Donna Willoughby, Amy Papile. Left to right, front row: James Cuddy, Iqbal Masih, and Jen Brundige. |

The implications for educators seeking to kindle student interest international economics, or any other subject for that matter, would seem to be fairly clear. "A School for Iqbal" was a sustained, multi-year effort by the Broad Meadows students who managed to see their project through to the end with little, if any, prompting. Their teachers introduced them to the wider world and offered them guidance. The students then applied themselves and took the learning experience to the next level. If Mr. Adams had simply lectured them on child labor, "A School for Iqbal" might never have been built. By arranging for Iqbal to visit Broad Meadows, he put a human face on an issue that melded international economics with human right concerns and, in the process, engaged his students' interest in a real-world issue. But, of course, they went beyond that, and their efforts inspired and captured the imagination of people far beyond the walls of Broad Meadows Middle School. For more information on "A School for Iqbal," visit the campaign's web sit: www.digitalrag.com/mirror/iqbal/index.html |